CHAPTER XVIII: The Recovery Process

The last few paragraphs have anticipated the most important and essential part of Re evaluation Coun sel ing theory: The process of damage and loss caused by distress experiences can be reversed and the lost intelligence and abilities can be recovered.

Human beings are equipped inherently, not only with vast intelligence and capacity to enjoy life and other people, not only with the susceptibility to hav ing this endowment damaged and limited, but are also equipped with damage repair facilities, healing pro cesses. These processes undo the effects of hurts im mediately after the hurts happen, they remove the stored distresses immediately after they occur when ever they are allowed to work.

These damage repair processes, at least the outward manifestations of them, are very familiar to all of us. Everyone has experienced them and has observed them but all of us have been so thoroughly conditioned that it is very difficult for us to think about them, especially when they are present and operating.

To think about these fundamental healing pro cesses, consider a new, unconditioned human being, an unhurt infant. Consider this infant to be in a very special environment. This environment is to consist essentially of caretaking adults who are so free from the usual accumulation of hurt patterns that they are able to be relaxed and undistressed when the baby is dis tressed, that they will not become upset by the baby's upsets.

Adults so free from rigid reactions towards a baby in distress do not exist, at least in noticeable numbers, in our general population. All of us have accumulated too many hurt patterns by the time we are adults. Nevertheless, this condition has been ap proximated by adults who have freed themselves of substantial quantities of their accumulated distresses through Re eval uation Counseling. The overall de scription of what happens will not be hard for the reader to credit because it will fit his/her own experi ences.

If this new, still human baby who has these relaxed adults in his surroundings happens to meet an expe rience of hurt, the process of hurt storage takes place as we have described. Let us suppose that he loses his mother in a crowded downtown street for about ten minutes, and that this is a deeply distressing ex peri ence even though a short one. Let us further sup pose that Mother returns at the end of the ten min utes, that the bad experience as such is ended at this point.

Now if Mother is as we have hypothesized --re laxed, aware, attentive, and undistressed-- if she gives to the baby her aware attention and concern, gives him her arms and eyes but keeps her mouth shut and does not talk, sympathize, jiggle, distract or interfere, then the damage repair process of the baby goes into action. Without hesitation, spontaneously (no one has to tell the baby what to do) he turns to this attentive mother and begins to cry. Allowed to do so, he cries and cries and cries and cries. He will continue to do so for a long, long time if every time he slows down and looks out at his mother he finds her still interested, still attentive, still caring, but not interfering or distract ing.

He will cry and cry and cry for what will seem to be a very long time and then he will be done, really done. Now the baby will change remarkably. He will resurge to obvious happiness, to great enthusiasm and alertness, to awareness and outgoingness and ac tivity. This process is very exciting to observe. The freshly discharged child is an impressive picture; one feels as if the clouds have parted for a moment and the real human being is showing through.

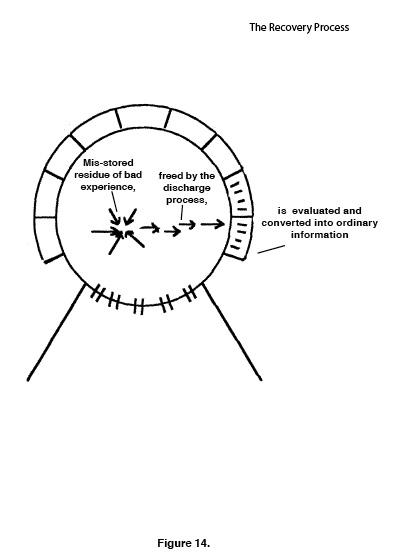

Apparently the profound healing process of which the tears are the outward indication has drained the distress from the mis stored bad experience residue and the baby's mind can now get at the information itself, perceive what actually happened, and finally eval uate it, make sense of it, understand it. The mis storage becomes converted to ordinary information, is stored correctly, becomes available to help under stand later experiences with in the usual way. The rigid responses which had been left by the bad ten minutes are gone. The recording is no longer available to be triggered by later incidents. The frozen portion of the baby's mind is free to work again. (Fig. 14)

You can check the alternative from familiar experi ence. If the baby does not get a chance to cry thor oughly enough and get the bad experience "out of his system" completely, his mother can expect the upset recording to be triggered the next time she tries to leave him with the babysitter. If he did cry out his dis tress thoroughly right after the bad experience, her leaving him next time will be taken in his calm stride.

Now consider another variety of distress experi ence. Suppose the baby is badly frightened. If he has someone to turn to who is able to be relaxed and at tentive and keep from reacting to him, then, once the fright is over, he will spontaneously begin to tremble, to scream, to perspire from a cold skin. He will persist in this for a long time if he is permitted to do so. He will check once in a while that the other person is still paying aware attention to him, and, reassured, will re sume the discharge. He will shake and perspire and scream for a long, long time and then he will be through. Again, as with tears, great alertness and well being will be evident after the trembling is all done.

If a baby is frustrated (and all babies are frustrated many times every day in the course of the usual han dling), she will discharge the frustration and get it out of her system if she is allowed to do so. If someone will really listen, she will discharge in what is usually con demned in our culture under the name of "tan trum." She will make violent physical movements and angry noises, and will perspire from a warm skin. This is exactly what she needs to do.

If the person present with her will hear her out, fully and with attention (undoing or removing the source of the offense first, if possible), she will go on yelling and flailing and perspiring for a long time. It will seem even longer to an embarrassed parent, par ticularly if it happens in public. If she is allowed to do so freely, however, and is not again frustrated in the effort to quiet her, she will come to the end of this dis charge also and will emerge a relaxed, happy and co operative child.

The child, who has been ridiculed or made to feel embarrassed in some way (and we all had this done to us many times when we were young) and then can turn to the relaxed, interested adult we have de scribed, will seize the opportunity to talk to the adult about the embarrassing experience. If the adult listens with attention and keeps her advice to herself, the child will narrate the embarrassing experience repeat edly and will finally attempt to joke about it. Soon, she will begin to laugh. She will laugh harder and harder as she returns to her narration. Finally, having laughed out her tension, she will walk completely free from the embarrassment that had gripped her to the point that she was afraid to face her associates.